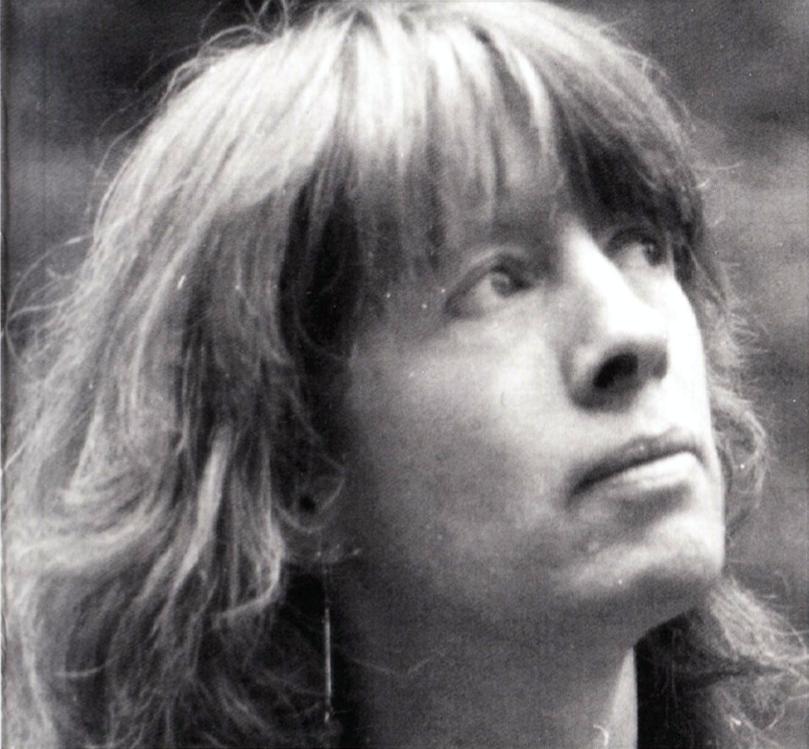

Lyn followed the objectivist poet Louis Zukofsky’s dictum that “the words are my life”; with Jackson Mac Low (1922–2004), she was arguably one of the great postmodern interpreters of the work of Gertrude Stein. Combining acute perception of language at all levels with a manifold curiosity toward experience and the world, both natural and political, her work developed as a consistent and ceaselessly inventive practice. Her most famous essay, “The Rejection of Closure” (1983), is readable not only as a discussion of form but also as a form of life that defers ending. Yet, at the same time, Edward Said’s concept of “late style” compelled her, and she was intensely productive over the past two decades—calling into question easy identifications of her work with its moment of emergence in 1970s San Francisco, or with the early success of My Life.

For the 51st annual Louisville Conference on Literature & Culture, held in February 2024, fellow Language writer Barrett Watten set out to organize, with eight peers and collaborators, a tribute to Lyn. Working with former conference director Alan Golding and current director Matthew Biberman, they wanted to create a spontaneous, ad hoc event that would illuminate multiple facets of her “life in writing.” The aim of the event was to emphasize Lyn’s hands-on work of supporting other writers, the multiple fronts on which she engaged, and the multiple perspectives from which her work can be read. As well, her volume of critical essays, Allegorical Moments: Call to the Everyday, had just appeared from Wesleyan University Press in November 2023, and we hoped to publicize that volume and its many critical angles. We wanted as “multiple” an account as possible.

In 2022, Lyn was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer, and she underwent a series of difficult medical interventions over the next two years. As the conference approached, we were told that she had discontinued treatment and had chosen to return home. No one could know how long she had left, but we could only assume, and hope, that she would be with us (virtually) for the event. Roughly 20 minutes before our presentations were set to begin, however, we received a text from her husband Larry Ochs that Lyn had died that morning. Stunned by the news, we had no thought but to continue.

The papers were delivered in the sequence that follows below, by Rae Armantrout, Kit Robinson, Carla Harryman, Alan Golding, Jeanne Heuving, Roberto Harrison, Vladimir Feshchenko, Abigail Lang, and Barrett Watten. As Rae Armantrout, who brought this work to LARB, puts it:

Her characteristic tone is that of an explorer setting off on a journey to strange lands and ready, eager in fact, to take interest in whatever presents itself. To read her is to go on a rollicking philosophical and picaresque adventure. Her work showed us how lived experience and intellectual curiosity can accompany one another.

It is our hope to offer these papers as an ongoing tribute to Lyn Hejinian’s extraordinary oeuvre and its radical influence on contemporary poetry.

—Barrett Watten, Rae Armantrout, and Carla Harryman

¤

RAE ARMANTROUT

On Lyn Hejinian

Lyn Hejinian was a great poet and a dear friend. From the start, she has participated, seriously and gleefully, in the long unwinnable argument between necessity (or fate) and chance. Despite the fact that one of her books is called The Fatalist (2003), I’d say she most often takes the side of chance. This means, of course, that she was both brave and patient. It takes both qualities to accept and welcome what arrives by accident. I want to read a passage from The Fatalist that will, I hope, show what I mean:

Come Tuesday.

Come spring. The light flickers

and figures. I’m safely home again provided

I adventure and consider fate

as occurrence and happenstance as destiny. I recite an epigraph.

It seems as applicable to the remarks I want to make as disorder

is to order.

Lyn was able to conduct both sides of such an argument because she possessed both a rigorous intellect and an unbounded imagination. She was “launched in context,” to quote a motif from The Beginner (2002), and, once launched, took the twists and turns that present themselves with an appreciation for the absurd and a keen sense of humor. It’s a road that has led her to fable, children’s poetry, and the picaresque. This poem in The Book of a Thousand Eyes (1996) is just one example:

The twenty-third night was very dark.

It was cold.

My eyes were drawn to the window.

I thought I saw a turtledove nesting on a waffle

Then I saw it was a rat doing something awful

But anarchy doesn’t bother me any more than it used to

I thought I saw a woman writing verses on a bottle

Then I saw it was a foot stepping on the throttle

But naturally freedom can be understood in many different ways

I thought I saw a fireman hosing down some straw

Then I saw it was a horse grazing in a draw

But it’s always the case that in their struggle to survive, the animate must be aided

I thought I saw a rhubarb pie sitting on the stove

Then I saw it was the tide receding from a cove

But although I have strong emotions when I watch a movie, jealousy is never one

of them

I thought I saw a bicyclist racing down the road

Then I saw it was a note, a message still in code

But sense is always either being raised to or lowered from the sky

I thought I saw a gourmet chef smear himself with cream

Then I saw it was myself just entering a dream

But we all know that the imagination when left to itself will brave anything

I have always turned to Lyn, in person and in print, for this combination of equanimity and élan.

She loved the unexpected, yet she also says in My Life, “I try to find the spot at which the pattern on the floor repeats.” There can, after all, be no variation without pattern. In a more recent book, The Unfollowing (2016), Lyn wrote about the ultimate break in pattern—mortality. This book is composed of elegies, unconventional sonnets, each 14 sentences or phrases long. Each sentence after the first is a non sequitur. I’ll read the first third of #57:

Useless lighthouse, and the bucket on the beach, the tattered begonias

Forget examples—there’s not an entity or detail around that isn’t more

than a mere example

What’s truly funny?

Once upon a time there was a mouse, and there was a cactus and a pair

of very small rubber boots with a hole in the sole of the left one, and

now that I think back I remember that there was a baby on a barge in

a lake full of flowers, and out of these there’s a story to weave and

probably more than one

The music changes at the mantel, the bassoonist is baffled, the

synchronizer fails

This retrospective plenitude is both comical and somehow heartbreaking.

Lyn encouraged and inspired countless writers—and I am definitely one. I want to finish with an old favorite of mine—the first poem in The Cell (1992). It is full of Lyn’s characteristic verve, and then stops at a perfect/imperfect ending:

It is the writer’s object

to supply the hollow green

and yellow life of the

human I

It rains with rains supplied

before I learned to type

along the sides who when

asked what we have in

common with nature replied opportunity

and size

Readers of the practical help

They then reside

And resistance is accurate—it

rocks and rides the momentum

Words are emitted by the

rocks to the eye

Motes, parts, genders, sights collide

There are concavities

It is not imperfect to

have died

¤

KIT ROBINSON

Words for Lyn

I had hoped that Lyn would be able to view this event, if not now then at least later. The news of her death comes as a great shock. Ahni and I brought soup and visited Lyn and Larry on Sunday. It was wonderful to be with them. Lyn was in good spirits.

My first memory of Lyn is of her reading at the Grand Piano in San Francisco soon after she and Larry moved to Berkeley from Mendocino County. She was wearing a light brown suede jacket that matched her hair color, and she had a pleasant, smiling, self-confident manner. Lyn and Larry’s house became a hub for poetry work and social life. That’s where she cranked out the 50 letterpress editions of the Tuumba chapbook series and where a group of us rehearsed Louis Zukofsky’s multivoiced “A”—24 with Bob Perelman on piano.

Lyn is a master of expository prose, writing about writing with a sharp critical mind while incorporating the wildness of her poetry. Her talk on “the rejection of closure” was early evidence of this talent, which would lead to teaching positions, first at New College of California and later at the University of California at Berkeley. As a teacher, she was a tremendous role model for aspiring poets. Her students have gone on to brilliant careers both inside and outside academia.

In 1978, Lyn and I hosted a weekly radio program called In the American Tree: New Writing by Poets. Our broadcasting chops were nil, but we learned as we went along and had many interesting conversations and readings by poets such as Ted Berrigan, Joanne Kyger, Bobbie Louise Hawkins, David Bromige, and Robert Grenier.

From October 1986 to January 1989, Lyn and I carried on a correspondence, trading 12-line poems in the mail. The first set of 24 poems was published by Charles Alexander’s Chax Press in a beautifully designed letterpress accordion-fold edition called Individuals (1988). Lyn later published an expanded version of her side of the series entitled The Cell.

In 1990, Lyn invited me to go with her, three other American poets, and five Russian poets on a US State Department–sponsored tour of Stockholm, Helsinki, and Leningrad. A week in Leningrad was like a lifetime in another world, the flip side of our American existence. I wrote, “Lyn is indefatigable, charged up, on. In Russian her speech is more direct, less intellectually elaborate.” Back stateside, we met evenings to work on my translation of Ilya Kutik’s 60-stanza Ode on Visiting the Belosaraisk Spit on the Sea of Azov (1995). Without Lyn I could never have done it.

In the 2000s, as Lyn’s academic career and mine in the tech industry kept both of us on the run, we met frequently over wine at a revolving set of bars in Berkeley and Oakland for camaraderie, gossip, and fun. As always, I was knocked out by her natural generosity, keen intelligence, and lively wit, all of which may be found in her voluminous work.

From Positions of the Sun (2018), chapter 11:

People speak of false starts. Jumping the gun, coming to a conceptual dead end, getting nowhere. In the wake of the false start, it’s assumed that a better start will take place, a true beginning, whose success lies in its continuing on until it comes to its proper conclusion and brings something about. Stray ideas, then settlement, gymnastics, topographical maps, similes, a hardboiled egg—a real egg, still warm, chopped, and spread on a slice of buttered sourdough toast—all unabstracted from their common material context: a summer morning, a specific one, which, like a dream, holds out incidents under tension. Water is spilling onto the floor. A hole breaks open in the ceiling, and gooey, acrid, wet plaster falls on my face. I open my mouth to say something—what would I have said?—globs of the goo fall into my mouth. I bend forward and vomit into my hands. This season, which is fast disappearing, will not turn out to have been a tell-all time. But for awhile during it everything was permissible—lies, fake IDs, polylingual melodramas, an invasion of pantry moths. Much of everyday life (murmuring repetition) goes on invisibly, including the tendency to fantasize, to plan or perseverate, to feel oneself to be in the right or in the wrong, to imagine changes (or changing). Even to dream of insurrection, or to live contradictorily, against one’s class background, say, and against one’s education, and pretending to be, like many tellers of tales, born from the dark and the daughter of a goose. Detlev Claussen, writing about Adorno, says, “The idea of happiness continues to live off the ahistorical moment of the absence of contradiction.” Such an idea (or experience) of happiness emerges from one’s being in accord with whatever happens—from one’s amor fati. It is a form, albeit an active one, of fatalism. There’s no reason to take fatalism here in a solely derogatory sense. But “all’s for the best” is not synonymous with “all’s for happiness” or “all provides happiness.” Everyday life (shafts of repetition) is a matter of brute force and great delicacy. […] Along comes sudden sunlight, intruding on my attention: sudden sunlit intrusion. Sun on inanimate objects that determine my experience of the day: sun on a striped glass of orange juice, on a pair of scuffed flat misshapen (or reshaped to my needs) black shoes, sun on my veined and mottled right hand, sun on the newspaper.

¤

CARLA HARRYMAN

from “Notes of Time: An Epistolary Collaboration

(January–December 2023)”

Allegory depicts what has been undepicted in a depiction. To do so it cannot proceed except across temporal gaps.*

Dear Carla,

A new calendar year has begun. To relocate ourselves temporally, and especially to situate ourselves in the future, project fantasy onto the screen between the present and the future. There’s plenty of fantasy behind us in the past too, of course: once upon a time there was a princess who had turned into a crow—or, worse, a crowbar.

Dear Lyn,

We imagined sewer lines traversing the road, but now our thoughts are redirected to a more local vent.

Perhaps art is hypothetical in the time of writing. It is not yet known what it will be.

[Allegory] seeks to dig into time, to secure a place for what’s gone and for what’s not gone, the loss itself.

Dear Carla,

I paused before writing “and to the historical moment”; I find myself repeatedly expanding contextual frames until they become so enormous, so comic, as to be absurd. It’s impossible to think of anything in terms of everything. And yet it seems inadequate and irresponsible not to do so—or just too limited, too exclusive. And exclusivity doesn’t exist in the future except as an inevitability.

Dear Lyn,

I have no trouble with the idea of the historical moment. It’s a concept that offers a means of sharing, reflecting on, and communicating what’s happening now—of testing how we are experiencing the present and how we address that separately and together, differently and similarly.

For Stein, something like geological time had to suffice—the magisterially slow, for which human velocities and their attendant anxieties are a mere foil.

Dear Lyn,

When you consider change a better term for time, are you thinking about Henri Bergson’s duration and qualitative experiences of time in distinction from clock time? I keep tiptoeing up to what I might write about “the clock.” In my poet’s theater works, there are only rare instances in which time is strictly regulated, but in Hannah Cut In, the performance is regulated by the clock. There is in this piece a need to sustain an immediate relation to clock-time that will arrive at a cutoff. Rather than pressuring the performer to concentrate on ending or goal, this rather causes one to be present to time and timing in the moment. Like a carnival ride, the scene will end no matter.

Dear Carla,

[A] change I’m referring to is climate change—or the environmental catastrophe for which climate change is essentially a euphemism. We say (and often complain) that time is speeding up. I wonder if somehow we are also experiencing time now as becoming more extreme. Perhaps so, even if only to the extent that we find that the present—each present moment—is becoming increasingly intense.

Today the affective responses to temporal pressures that we experience seem so similar to guilty or obsessional unease as to suggest that we are currently interpreting time as a province in which we are expected to meet standards and fulfill obligations that are beyond our capacities.

Dear Carla,

For a year or two (back in the late 1970s, I think), I routinely wrote down my dreams every morning and added footnotes to each dream account supplying the real-life originals of the dream events or images. Eventually this became an obsession: I was so afraid of forgetting a dream that I didn’t dare fall asleep, which of course meant that I didn’t have any dreams, either to remember (and record) or to forget. I literally got too tired to sustain the project, though I think I have a copy of the whole thing somewhere. As I think about it now, the dream project seems to have entailed something a bit like unfolding napkins.

Like Heidegger, Oppen intuited that being is always a being-in-time, that things are always things-of-time: “Her ankles are watches.”

Dear Lyn,

As you have mentioned, when you first posed the question about the future, you were thinking about art, even as you ended your opening gambit with a question, “Why aren’t there futurity classes everywhere?” But just previous to this, you wrote, “Perhaps it’s not inaccurate to say that art is hypothetical. That would keep it future-bound. As for what I think writing, or art more generally, might provide for time—how it might affect or simply exist in the temporal past, present, or future—that remains an open question.”

Of course, one way to discern the contours of this open question, what “art […] might provide for time,” is to draw out what is significant to you in what it has provided for time. I would say that Allegorical Moments could be thought of as a transhistorical tapestry work that provides concrete examples through which the question you pose resonates. But in the question regarding what “writing […] might provide,” I sense that you are mulling on precarities. Precarity is a circumstance that places us on the precipice of an unwanted future and another future that may delay or transform this (futureless?) state.

*The segments in italics are from Allegorical Moments: Call to the Everyday.

¤

ALAN GOLDING

I want to begin my contribution with an allegorical moment from 2003, the year that Lyn Hejinian keynoted at the Louisville Conference, and that moment involves a previously unpublished piece of Hejiniana revealed here for the first time. As many of you will know, in those days, my wife, Lisa Shapiro, and I hosted a post-conference party, and part of our practice was to ask visiting poets to decorate an article of clothing, usually one of our kids’ old T-shirts. Lyn wrote/drew a stick-figure film in seven frames, a film titled, with ludic literalness, “Shirt: A Film,” with the further clarifying tag “A documentary by Lyn Hejinian.” Outside the frame of this playful shirt-film, she drew a surrounding context or landscape made up of shapes that hover somewhere between asemic writing and natural forms, with the one legible word “soundscape.” So, a generically hybrid T-shirt: film, narrative, comedy, documentary, sound, word play, a capacious definition of writing—the quintessential Hejinian production. For my second allegorical moment, it seems appropriate to revisit a specifically Louisville one—my introduction to Lyn’s 2003 keynote reading at this conference, lightly reconfigured for this occasion:

“This is a good place to begin.” Self-reflexively enough, that’s the first sentence of Lyn’s mid-career work The Beginner. Early detractors of Language writing criticized it for being overly sober, earnest, crankily theoretical. One often wonders whose work they were reading, and they certainly weren’t reading Lyn Hejinian. You’ll all recognize the point at which, like most kinds of love and joy, one’s love of and pleasure in a particular writer’s work staggers into inarticulacy when one tries to account for it. We’ve all been there. “Who’s your favorite poet?” Like a rat drawn to poisoned cheese, you go for the bait and name someone. “Why?” [Stammer noises.]

But I use the word “love” advisedly, and I find myself called to it by Lyn Hejinian’s work. None of that work is reducible to summary or essence, and yet I’m tempted to think of love as one of its animating forces: love of language, of verbal construction in all its material, psychological, and social ramifications, love of the processes of knowing. I stress “processes” because that plural term also seems to me central to Hejinian’s writing: it underlies the distinction between thought and thinking in one early book title, A Thought Is the Bride of What Thinking (1976), between the Faustian acquisition of knowledge and the making of knowledge through acts of verbal construction, the work of La Faustienne. The epistemological concerns that animate her work are captured in some of her essay titles: the now-classic “The Rejection of Closure,” “Strangeness,” “Reason,” “The Person and Description,” the wittily inflated “The Quest for Knowledge in the Western Poem.” As she puts it in stating a key premise of her poetics: “The language of poetry is a language of inquiry.”

No surprise, then, that Lyn should ask, in My Life, “Isn’t the avant garde always pedagogical”?—a formulation that I’ve found sufficiently thought-provoking to already steal it for the title of an article, a couple of graduate seminars, and a book manuscript in progress. Such are the dark processes of assimilation that you have to deal with if you insist on producing that anomaly, the avant-garde bestseller. But My Life is just that, a radically alternative model for writing and thinking about the self and one of the genuinely lasting and most widely read products of the Language writing moment. It may be my life, but it’s also become everybody’s autobiography.

In Lyn Hejinian’s work, the unbearable lightness of being meets an unmatched particularity of attention. “There are things / We live among ‘and to see them / Is to know ourselves,’” wrote one of Lyn’s own beloved poets, George Oppen, including in those “things” the things of language, sound and syntax. The construction of gender in language and the historical processes of changing usage are compressed into one devastatingly simple sentence: “The postman became a mailman and now it is a carrier.” Oppen would have appreciated the weight that that “it” is able to bear.

In Lyn’s Slowly (2002), we encounter this sentence:

Lamplight and strange diction and the duration that’s required for something very ordinary to occur (the rice to cook, the rain to fall, the dust to dull the stripes of the zebra immobilized in a museum diorama as if to highlight our knowledge of zebras) are of course of interest of necessity.

Here we find the attention to the ordinary and the particular rhythms created by coordinating conjunctions and appositives that mark much of Hejinian’s work and that we also associate with Gertrude Stein. Meanwhile, the immobilization of knowledge is precisely what these rhythms are directed against, while the long parenthesis in which that immobilization is framed creates its own slowly unwinding duration that is, in an appropriately reiterative anaphora, “of course of interest of necessity.” So, one more time: “Lamplight and strange diction and the duration that’s required for something very ordinary to occur […] are of course of interest of necessity.” The things of this world, language choices, duration—crucial points of reference in thinking about Lyn’s work.

This is a good place to end, or for all of us to begin again and again. “As for we who ‘love to be astonished,’” Lyn’s work will continue to astonish us most pleasurably and instructively long into whatever futures await us.

¤

JEANNE HEUVING

Tribute to Lyn Hejinian

When it was first published, I read Lyn Hejinian’s The Language of Inquiry (2000), a brilliant set of essays on poetics, as if it were a divination. I later invited Lyn to a conference I organized on the subject “What is Poetics?” where she gave her essay, “An Art of Addition, an Eddic Return,” now included in a book I co-edited with Tyrone Williams, Inciting Poetics: Thinking and Writing Poetry (2019).

First, a personal note of thanks for Lyn’s generosity of spirit. As I was creating Inciting Poetics from the conference papers, the project foundered in its initial review stage. While a few people elected to withdraw their essays as Tyrone and I turned the conference papers into a book, I found Lyn by my side. She insisted, “You created this gathering, you made it happen, so you need to make something of it.” She had been enthused by the event itself, and the thought that it would not become a book seemed wrong to her. She was concerned about my efforts and my energies—that they not be wasted. I found it surprising that she should be concerned not so much with whether the book was published or not but with the work I had done in organizing and creating the conference. My work and the enthusiasm about poetics that emerged from this event, she felt, should not fall by the wayside. Her concern for me and for the event I created has stayed with me these many years later. I was emboldened by it to carry on, as I am sure Lyn has emboldened others.

In her essay “An Art of Addition, an Eddic Return,” Lyn engages a medieval Icelandic work, Snorri’s Edda, glossing edda as a poetics. The Edda, the poetics, was available centuries before the poetry on which it was based surfaced—a work that was honored and consulted, an art form in its own right. Lyn was astonished by the Edda because of the chronological order of the composition of its four chapters, which, as she recounts, began with the most material manifestation of the verse, and only in the last iteration moved into larger historical and cultural considerations. As Lyn emphasizes in the essay about her own practice, her poetics were an answer, an attempt to understand the poetry of her peers. Poetry in all of its unassimilable particularities came first, and the largest generalizations needed to be based on these particularities. Of the Edda she writes:

Snorri first wrote the startlingly various compendium of skaldic verses; when they were received with only minimal comprehension and appreciation, he wrote his analysis of poetic language; when this didn’t help matters sufficiently, he wrote out the collection of folk tales and myths to which those verses refer; and when even that wasn’t enough, he historicized and localized those myths to establish incontrovertibly their contemporary relevance to readers of his skaldic verses.

In defining poetics itself, she writes,

Poetics is always in an unbounded, excessive relationship to its art, which may in part account for the difficulty one has in defining the term. It is more than theory and more than practice; it is what identifies an artist’s largest aspirations and discovers the ways those become manifest—the ways they are activated and provided with the manner in which the artist applies him- or herself to realizing those aspirations and, when lucky, something more besides—expanding, perhaps by virtue of their inherent contradictions, between affect and structure, materiality and sensibility, aspiration and patent failure, ostensibility and abstraction, assertion and silence.

¤

ROBERTO HARRISON

your fearlessness grows for the ground

for Lyn Hejinian

from every morning through the night

you are here inside the pages made to shape

and frame a sentience with and without words.

you move inside a kindness with the real of life,

in everything you write the letters now and then

that I receive and will again return to light myself

to every poem, every word. your letters with

my letters, bring us there because you hear

me once and every time with moving climates

there within you, inside my opposition

to the world. your attention like a wilderness

with my sorrowful connections prove that you

are not behind a screen. I find you here and you

receive me, I speak and then you hear me,

and I walk with you beside me there

in other countries, other places, where I was

and where I struggle to become. I was overcut

for many years and then you made things vast

with light, you help me see …

I am a jaguar in the time to start, I am

a snake to be alone, I am the cockroach

meant to heal the past with consciousness

extended to belong with life. and I am only one of many

you embrace. I am the smaller caption of a country

by my side where you arrive to be an arrow, with oars

and lines becoming jungles. through you I glimpse

a world of possibility, I taste real exits from before

as I begin to burn the shade through vibrant colors

and you now bring us back to earth for more

¤

VLADIMIR FESHCHENKO

Lyn Hejinian is a paramount figure bridging two major experimental cultures in poetry of the last decades—American and Russian. Her visits to Soviet Russia, from the early 1980s, gave rise to prolific contacts between “Language poets” in the US and “metarealists” in Russia—contacts that still persist, in spite of all historical obstacles. Her famous visit to Leningrad in 1989 with other poets of the school was perhaps the first collective exchange in history between Russian and American poets, a meeting that familiarized and at the same time defamiliarized the two poetic traditions in their creative avant-gardism.

Lyn’s affinity with Arkadii Dragomoshchenko grew into many years of friendship and cocreation. For several years, they carried out a joint correspondence project—The Corresponding Sky. Lyn translated two of Arkadii’s books into English and contributed to the translations of other Russian poets. In turn, her texts found Russian readers thanks to Arkadii and his circle. Both poets—Lyn and Arkadii—are sensitive to the similarities and differences of each other’s languages. Lyn explained the radical difference between English and Russian not only by the movement of thought but also by the foundations of thinking itself; in an interview with Dubravka Duric, she noted: “American is a wide language, with enormous horizontal scope, and Russian is a deep language, with enormous vertical scope. Our metaphysical worlds are very different.” Yet, in the interlingual American–Russian transfer between the two poets, “width” resonates with “depth,” opening up new dimensions of expressiveness. And language in Lyn’s works is an allegory of love, an allegory of passion, and an allegory of unity.

Last year saw the publication in Moscow of Lyn Hejinian’s bilingual book of selected writings, titled Masks of Motion—Слепки движения. In it, her texts become available to Russophone readers in their completeness and diversity. The book includes texts from early poetry books of the 1960s and ’70s up to her experiments in “immersive writing” of recent years. Lyn’s Language writing in all its poetic, narrative, and essayistic formats is always a test of the boundaries between prose and poetry, memory and fiction, objectivity and subjectivity. This volume, I venture to say, is the first and most extensive selection from all periods of her work, from different books, from all cross-genre variations. This is a collection of “masks of motion,” of her original “writing-as-inquiry.” Her “book of a thousand eyes” translated into the language that was the closest to “her life” after her native English.

¤

ABIGAIL LANG

Une pause, une rose, une chose sur du papier: For Lyn

Barrett asked me to say a few words about Lyn’s French reception. As I was assembling material, I kept thinking of this phrase—“Lived life is only details”—something Lyn said during the two-day symposium that Vincent Broqua, Olivier Brossard, and I convened to discuss her work in early 2020, and which strikes me as extremely Hejinianesque in the way it resonates with her urge to “let everything into” the work, to possess one’s life, and to experience experience.

So, before waxing factual, I will begin with one personal detail, evoking the combination of insight and delight I received from her letters in the Archive for New Poetry at UC San Diego, in particular her wonderful correspondence with Susan Howe, in which they share thoughts about the books they read, their writing projects, motherhood and domestic life, travels, and the poetry world, offering insight into poetics and group formation but also the texture of a life lived.

Change

In 1981, the magazine Change, an offshoot of Tel Quel, published a “Poésie Langage USA” feature that included poems and statements (later reprinted in In the American Tree, ed. Ron Silliman, 1986) by seven Poètes Langage, together with a presentation by Nanos Valaoritis. Pages from Writing Is an Aid to Memory (1978) and My Life were translated by Jean-Pierre Faye.

Tarascon

In the summer of 1988, the Festival de Tarascon in Provence invited five Language writers for a reading: Charles Bernstein, Bruce Andrews, Lyn Hejinian, Susan Howe, and Ron Silliman. Lyn met Liliane Giraudon and Jean-Jacques Viton, who published the magazine Banana Split and co-organized the festival.

Royaumont

In 1989, poet Emmanuel Hocquard organized the first conference on the Objectivists at the Fondation Royaumont in the outskirts of Paris. The conference contributed to the recognition and canonization of the Objectivists and sealed a Franco-American friendship on the grounds of a common lineage and a certain interpretation of these ancestors. Lyn presented on Zukofsky and went on to give readings in Paris and Marseille.

49+1 Nouveaux poètes américains

Emmanuel Hocquard and Claude Royet-Journoud published two anthologies of contemporary US poetry in 1986 and 1991. The second one featured excerpts from The Cell, translated by Marie Borel and Jacques Roubaud, and an “Elegy” translated by Françoise de Laroque. Of the 49 US poets featured in the anthology, “only” 29 also appeared in In the American Tree, making for a highly unusual grouping from a US standpoint, as Hejinian explained to Royet-Journoud (on January 19, 1992):

I heard reports from both Michael and from Susan Howe about their trips to France (or the suburbs of Paris) in the fall. And 49+1 arrived very soon after that. It is for me a fascinating volume, presenting a picture—a snapshot, presumably—of American poetry from a very unfamiliar vantage point. Since I like everything unfamiliar—and especially defamiliarized versions of familiar things—I like the book. I know all the poets, but I have never imagined them all together in just that way. Is it really a French view of contemporary American poetry—or, as I suspect, is it a lovely and perhaps rare snapshot—an unusual instant, randomly captured?

Come to think of it, I imagine Paul Auster’s Random House Anthology of 20th Century French Poetry might have seemed peculiar to you.

Jour de Chasse, trans. Pierre Alferi, Les Cahiers de Royaumont, 1992

In 1991, Lyn Hejinian and Leslie Scalapino were invited to the Fondation Royaumont for a collective translation seminar. Poet Pierre Alferi finalized Jour de chasse. Roman russe, a translation of 45 chapters of the long poem Oxota (1991).

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Pierre Alferi and Lyn Hejinian read each other’s work and corresponded. Alferi found inspiration in My Life’s “daring and clever technique,” while Hejinian published sections from Chercher une phrase (1991) in Poetics Journal and “stole” from Le chemin familier du poisson combatif (1992), disguising her thefts as mistranslations. “Maybe we have in common an interest in ‘doing philosophy’ in poetry,” Lyn writes Pierre.

Lentement, trans. Virginie Poitrasson, Bordeaux, Format américain, 2006

In 2006, writer and translator Virginie Poitrasson translated Slowly (2002) as Lentement, which was issued by Juliette Valéry in her Format américain series. In an account of the translation process, Virginie notes how Lyn’s insistence on the literal meaning freed her from a purely semantic translation and emboldened her to follow the fluctuating rhythm of the text.

Gesualdo, trans. Martin Richet, Marseille, Éric Pesty Éditeur, 2009

In 2009, Martin Richet, a prolific translator of US avant-garde poetry, published his translation of Gesualdo (1978) with Éric Pesty Éditeur. While Hejinian’s Gesualdo served as the structural and syntactic matrix for Rosmarie Waldrop’s book Differences for Four Hands (1984), Richet’s French translation prompted Marie-Louise Chapelle to write Tu (maniériste), published by Éric Pesty in 2017.

Ma vie, trans. Abigail Lang, Maïtreyi, and Nicolas Pesquès, Dijon, Les presses du réel, 2016

I started translating My Life in 2007, for a reading Lyn gave in Dijon with Dominique Fourcade, and completed the translation in 2016, in collaboration with Maïtreyi and Nicolas Pesquès, with whom I had previously translated Lorine Niedecker’s late work. In both cases, we began translating unaware of each other’s endeavor and decided to join forces, becoming friends in the process.

L’Insuivant, trans. Chloé Thomas, Nantes, Joca Seria, 2022

In 2022, writer, translator and scholar Chloé Thomas translated The Unfollowing (2016) for Olivier Brossard’s Collection américaine at éditions Joca Seria. Lyn’s work has received scholarly attention from several French researchers including Chloé Thomas, Marie-Christine Lemardeley, and Hélène Aji.

Centre international de poésie, Marseille

Twelve Tuumba chapbooks are currently on display in an exhibit showcasing the collection of US poetry held at the library of the Centre international de poésie in Marseille. In 2021, a young artist named Clara Degay devoted her master’s thesis in fine arts to Tuumba press. I take this as an indication that Lyn’s reputation, already firmly and happily established in France, is being amplified by a new generation of writers and artists.

I now hand over to Barrett and send Lyn “une pause, une rose, une chose sur du papier.”

¤

BARRETT WATTEN

from “The Poetics of Refunctioning”

An author who teaches writers nothing teaches no one.

—Walter Benjamin, “The Author as Producer”

My point of departure is Lyn Hejinian’s Positions of the Sun, a hybrid prose work in 27 sections that tracks the “influences” and “affects” of a certain person traversing the day—when the sun is out and we are alive, when middle-class neighborhoods are humming with business, when theory and everyday life conjoin, but also when anti-capitalist riots and racial/class disparities haunt the present. The writing itself is a site of imagined, remembered, read, and mediated inputs and outputs, balanced to create an interrogation of their effectivity—a third (at least) major instance of the hybrid genres Hejinian has explored from My Life to A Border Comedy (1997). Walter Benjamin’s key concept Umfunktionierung (refunctioning) easily obtains in the writing of an elastic prose that accommodates materials from multiple genres toward a writerly synthesis: récit, memoir, theoretical essay, art criticism, political tract, shopping list, and so on. I will say also at the outset that Lyn Hejinian is one of my earlier literary collaborators; at the time of her writing Positions of the Sun, we were working on the multiauthored Grand Piano and A Guide to Poetics Journal, both experiments in genre, all of which involve crossing boundaries between authors, genres, and forms.

Positions of the Sun is a masterful assemblage of genre hybridity that includes 1) a repeated use of the terms “allegory” and “everyday life,” through citations of Benjamin, Henri Lefebvre, Michel de Certeau, and others; 2) a politics of the everyday versus the crisis of the university and Occupy, both audible offstage; 3) a refunctioning of historical events into the particulars of experience, a theory of history that rests in “chronology” as a formal baseline; 4) a foregrounding of chosen individuals to anchor its concerns (Charlie Altieri and Jean Day) versus the fabulation of up to 70 fictive characters as placeholders for the racial and class diversity of Berkeley and Oakland; 5) an insertion of lengthy descriptions of nature and visual art, such as the painting of Pierre Bonnard, along with quotations from major art historians; 6) a use of lists, from grocery shopping to every store on both sides of College Avenue in the upscale Elmwood District; 7) a form of mimesis in lengthy sentences that channel Adorno, critical theory, and “the essay as form”; 8) citations from world novels (Les Misérables and War and Peace), with discussions of literary realism; 9) theories of the avant-garde and the role of the reader; and 10) frequent mentions of the sun, where it is located in the sky, the beneficial effects of sunlight, the shadows that result, and so on. These are the motivated, not innocent, juxtapositions that, in a deficient reading, would suggest a univocal effect of refunctioned form—thus begging the question each element occasions. Hejinian’s experiment in genre and form appears to be a mediation through the materiality of writing, where its multiple sources find dialogue if not community in their mediation.

This “mighty recasting of forms,” after Benjamin’s key essay “The Author as Producer,” adds up to a universal blueprint composed of the forms of everyday life, amounting to a guide to what we live in the distressed present. But a mere focus on its “radical particularity” is insufficient:

How does a writer, or a serious artist of any kind, make it possible for someone to understand, and then to care about, what he or she is doing? It isn’t out of arrogance that the avant-garde writer doesn’t linger very long over the problem (if there is one) of accessibility implicit in such a question. One key goal of the historical avant-garde was to assert the primacy of art’s autonomy, from which would extend its authority and its self-evident right to significance. Inherent to the realization of that goal was resistance to external influences. “In the case of the avant-garde, it is an argument of self-assertion or self-defense used by a society in the strict sense against society in the larger sense,” as Renato Poggioli says in his seminal study, The Theory of the Avant-Garde (1968). “No, Fred,” Poggioli said.

In this passage, there is neither beginning, middle, nor end; neither crisis, catharsis, nor resolution; no moral conclusion other than the paradox of its metalanguage. The test case for Umfunktionierung, for Benjamin, was to put the author into production through the “mighty recasting of forms.” Here, a theoretical essay on the avant-garde, by Poggioli, is cast into the mold of subjective reflection as an avant-garde work—incorporated into the work itself, which seeks to be an allegory of the “outside.” It proceeds via a ludic evisceration of the author, a turning inside-out so that her vulnerability may be finessed by the work, so that anything can be said. The stakes are dilating, expanding out to include the reader’s response as incorporated.

The work’s point of departure in the Berkeley tuition struggles and Occupy in 2010–11 is kept at one remove. How, then, does such a refunctioned work “fight fascism”—Benjamin’s motivating concern? If we describe fascism, in a thumbnail sketch, as the weaponization of delusional personhood under conditions of massification, the passage forms a defensive wall against such aggression. It defeats fascism by baffling it, by absorbing it into a series of baffles. But the massification of that effect does not follow. Then what about the claim that such a passage is an “allegory” that draws out the meanings concealed in textual form? For Hejinian, the “forest of interpretations” assumes a material form, as identical to the situations that occasioned them. The refunctioning of the author puts the work resolutely in the world, where we cannot be deprived. Futural meanings are refunctioned as real-time effects. Such a poetics is a register, as well as a product, of the distressed present in which we live. And what is the distressed present? It is the task of the work to accurately describe it. The next question, then, to be posed is the status of description, which is a type of the practice of ekphrasis by which the manifold materials of the work are brought to a central, mediated and mediated, “I.” In describing the work and its purposes, “I” unfolds a parallel instance to the world at risk:

The sun is rising. Chuk-a-chuka-chuk, chuka-chuk, chuka-chuk. How we love it! The petals of the sun flare, waver, bend, spin. Someone sings. Light comes through a window, falls across a plate, illuminates the mottled surface of a shark’s tooth, a small red pocketknife. Humans are forever creating new allegories out of things they find in the world. A feather, a paper flag on a stick, and an ivory chopstick are stuck beside an upright tulip in a jar. Evidently someone has combed the rubbish heap, reevaluated some bits of debris, plucked them out of the limbo they’d drifted into when stripped of context, given them another moment. Aesthetic recontextualization brings things to a temporary halt, which is different from the false halt to which decontextualization had brought them.

This initial prompt is of overwhelming optimism; life is good even in the distressed present, and the sun is up to show us why. What the sun illuminates is the world of things, each in their particularity, and that is good too. Hejinian’s negative capability, to proceed in the final uncertainty of belief, is exemplary. But it also is an admission of doubt in her larger project in which she cannot have the final say. Totality awaits to dispose of us as it will, to “seek the gold of time,” in André Breton’s phrase. In our distressed present, we cannot reach totality; we can only be caught in the middle of things: our allegorical unfolding, which the work presents. In relentless pursuit of an experience that acknowledges the partial and emergent as the only experience possible, Lyn Hejinian comes as close to “the gold of time” as anyone who “is or was or will be living,” following her great predecessor, Gertrude Stein. That knowledge, the allegorical moment of “beginning, middle, and ending” in the unfolding of her capacious works, is her undeniable achievement.