PARIS — The late Hungarian-born artist Vera Molnár found patterns everywhere: in architectural details, in optic art, even in dreams. Spanning a remarkable eight decades of her 99-year life, Speak to the Eye, the Centre Pompidou’s compact yet ambitious exhibition of this little-known computer art pioneer, highlights her lasting fascination with geometry, disrupted perception, and technological experimentation.

After studying art in Budapest, Molnár settled in Paris in 1947, where she soon embraced Concrete Art. Her early color studies anchor the first galleries of this chronological exhibition and signal the show’s leitmotif of the artist’s fixation with the way we perceive patterns. In the painting “2 blue rectangles, 4 black rectangles” (1950), for instance, blue rectangles are enclosed in black ones, partly separated by bands of white space. Depending on one’s viewing angle, the black paint can take on bluish hues.

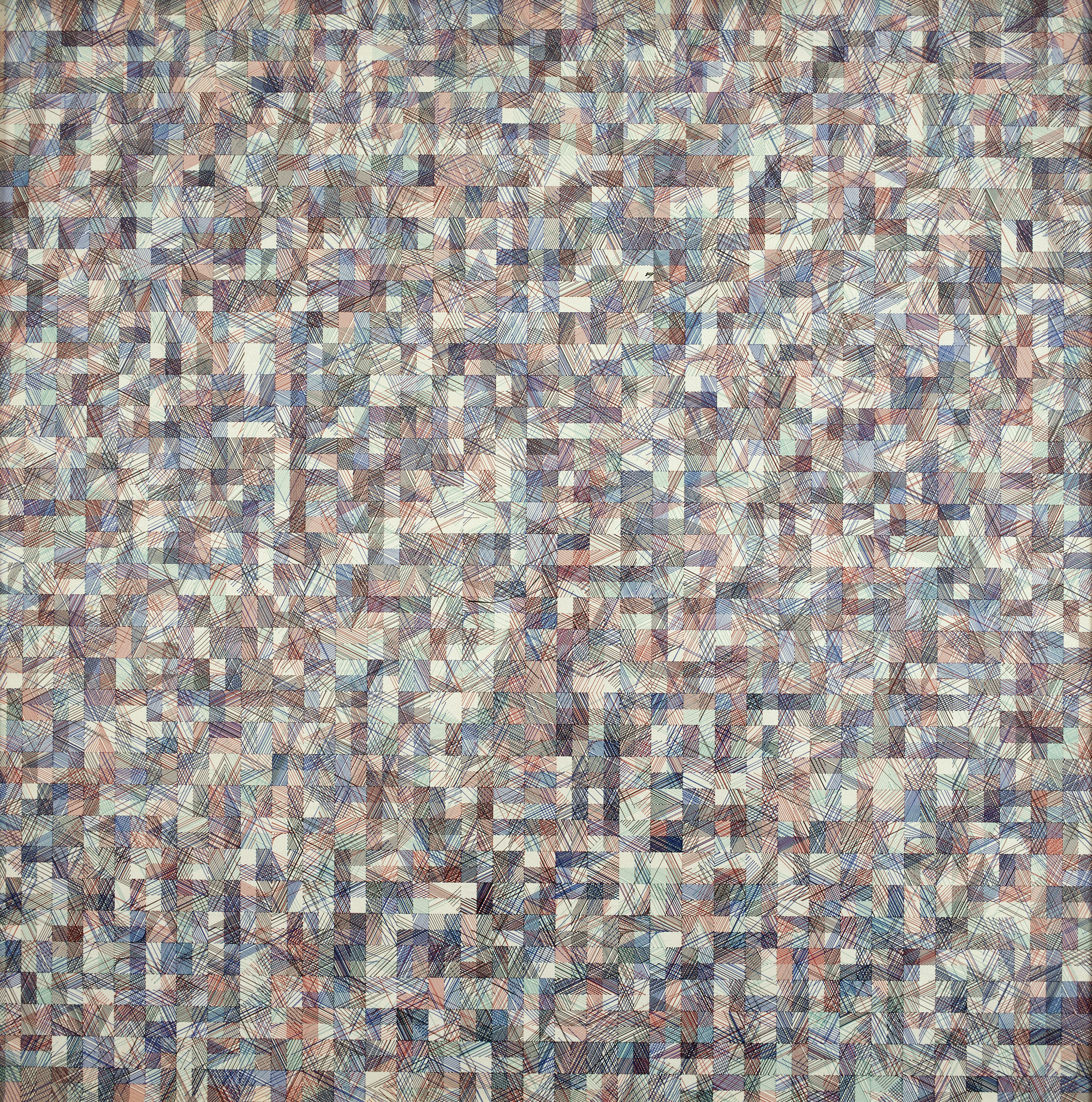

Starting with the late 1960s, algorithmic repetition takes on greater importance in Molnár’s compositions, hinting at her later use of computers. In a series of works, each titled “Looking for Paul Klee” (1969–70), orderly geometry is repeatedly disrupted by irregular patterns, resulting in the impression of a software program gone awry. Entries in journals Molnár kept between 1976 and 2020, gathered in 22 volumes displayed in glass vitrines, further demonstrate her relentless search for patterns. The title of one of her journals, Geometries of Pleasure (1985–87), also suggests her delight in playing with structure to a certain degree — and then letting her energetic lines and figures break out of the grid.

The devotion with which Molnár produced these fugitive entries suggests that she saw them mainly as a way to train her eye. Nevertheless, some of them were realized as full-fledged artworks. A 1987 collage for the Festival du Vent, an annual arts festival in Calvi, France, whose name translates to “Festival of the Wind,” explores the ways in which natural phenomena could be expressed geometrically. This work seems to give rise to the installation “OTTWW” (1981–2010), also featured in the exhibition, in which a black thread is stretched over nails in zigzags, the repetition of the letter “W” recalling a jumpy electrocardiogram.

In situating algorithms on equal footing with a plurality of media and supports, ranging from paper and thread to metal and mirrors, the exhibition suggests that Molnár saw the computer as a tool like any other. In her computer-based works, she seems to seek freedom within systematism and improvisation within predictability, in the vein of artists such as Kazimir Malevich and Piet Mondrian. In works such as “The Metamorphosis of Albrecht Dürer” (1994–2017), she designed algorithms that she then ran through a program, in this case one that incrementally changed the initials of the German artist to her own. Elsewhere, as in the painting “Trapezes or lines (1200{4c0343f45a07fa0dc8af450d54eddc29750e2d03fa627e961ccfaa8142e4e5bf})?” (1987–2014), she sets up a system of rules for herself, as if she were a machine. In other works still, Molnár engages the material embodiment of algorithmic design. Her recent metal sculpture “A perspective of a line” (2014–19), which she based on a computer-generated image, casts intricate slanting shadows in a lyrical, haunting play of light.

According to the exhibition catalog, Molnár was known to cite Paul Klee’s aphorism, “Art is an error in the system.” Perhaps the most exciting aspect of her art was this recognition that not even an algorithmic intelligence was entirely predictable — and her joy in finding in the glitch an affirmation of creativity.

Vera Molnár: Speak to the Eye continues at Centre Pompidou (Place Georges-Pompidou, Paris) through August 26. The exhibition was organized by the museum.