Why did it take them so long? The warning signs were clear to see. Long before the debate on June 27, Joe Biden was unpopular. Since September 2021 his approval ratings had been negative, and since early 2023 they had trended downward. In most pre-debate polls he ran behind an also unpopular Republican nominee.

Plenty of Democrats were queasy about running an octogenarian. Columnists sent public distress signals that echoed the private chatter. “I can only hope that when future historians look back on 2024,” Harold Meyerson implored in The American Prospect last November, “the question they ask isn’t ‘Why were the Democrats sleepwalking?’” But leading figures in the party mostly talked around the problem. “I think you got to be as public as you possibly can in addressing it, and that’s how you can settle it,” Montana Senator Jon Tester said in a typical response when Politico asked him about Biden’s age last October. In his February report on Biden’s handling of classified documents, special counsel Robert Hur described the president as a “well-meaning, elderly man with a poor memory.” Democrats dismissed it as a partisan stunt. As stories circulated of afternoon naps and vacant stares, the party and its elderly candidate stumbled on.

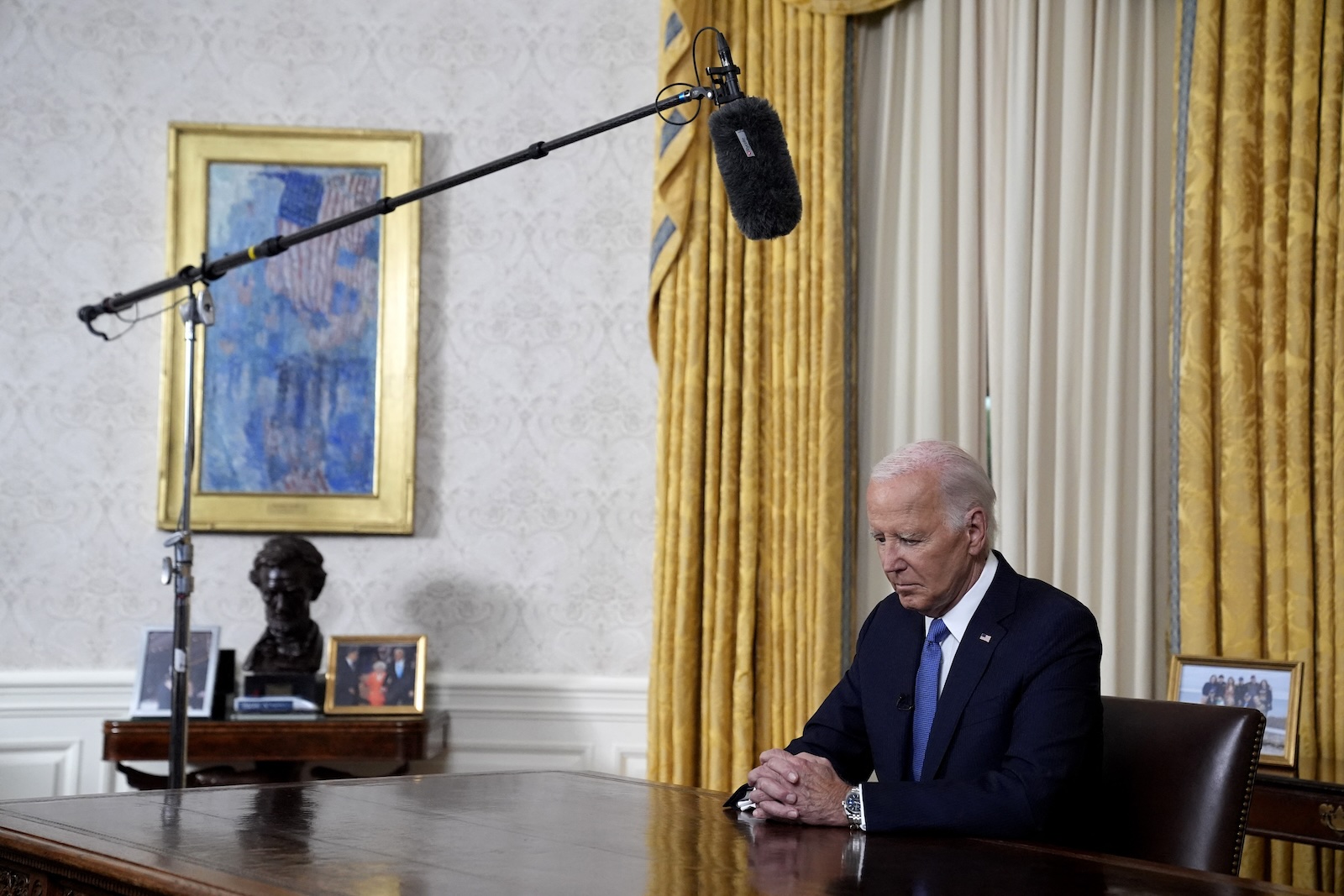

The debate changed everything. Biden’s incoherent performance rattled the entire Democratic firmament, from elected officials to leaders of interest and advocacy groups to big donors. The House of Representatives, whose members are all up for reelection, was the center of dissent. “Frontliners” in threatened districts sounded the alarm. “We just have too much at stake in this election to sit on the sidelines and be silent while we still have time to do something,” Hillary Scholten, who represents West Michigan, told The Detroit News.

The leading role fell to Nancy Pelosi, the former House speaker still serving in the chamber and three years Biden’s senior. After the debate, she began hinting that the nomination process was not, in fact, done and dusted. Whenever a member urged Biden to pass the torch, Hill watchers saw her hand. In early July Biden told George Stephanopoulos that only “the Lord Almighty” could make him step down. A Democratic strategist pointed to Pelosi: “Well, this is the Lord Almighty.”

Donors’ wallets dried up, most notably in image-conscious Hollywood. George Clooney expressed their disapproval in The New York Times. “It’s a crisis. The money isn’t moving,” a “top Democratic fundraiser” told Semafor. For his part, Biden called in to Morning Joe to say that he didn’t “care what the millionaires think”—just as polls began indicating that over 60 percent of Democratic voters wanted him to withdraw.

It was a halting and chaotic effort, but ultimately it was enough. On Sunday, July 21, the president, by some extraordinary turn of fate stricken with Covid, dropped out and backed Kamala Harris. The talk was thick that competitors would throw their hats in the ring, but they didn’t. Endorsements piled up fast. By the following day she was the presumptive nominee.

Is this what a functioning party looks like? As Harris basks in the pent-up enthusiasm, it’s tempting to believe as much. But in truth there was as much chaos as collective action. Caught in a prisoner’s dilemma, most party actors chose not to stick their necks out and risk the blowback, even knowing full well that they all needed another name at the top of the ticket. Biden might well have persisted if not for Pelosi. Hakeem Jeffries, the House minority leader, and Chuck Schumer, the Senate majority leader, held back, seeking to secure consensus inside their respective caucuses—and their positions at the top. To short-circuit a challenge on the convention floor, the Democratic National Committee (DNC) made specious arguments for a virtual roll call, in which delegates would vote online weeks before the event. (Citing potential challenges to ballot access, it has stuck with the plan.) Leading labor, environmental, and civil-rights groups were conspicuously absent at crucial moments. Democrats have united behind Harris. But they did not meaningfully “choose” her.

Over the next fourteen weeks of campaigning, the vice president may be able to do what the president could not—hammer home her opponent’s manifest weaknesses and underscore her own aptitude for the job. Now is not the time for introspection. But whether in victory or defeat, Democrats will eventually have to revisit the fervid summer saga that saw them, however messily, thinking and acting as a party—and ask themselves what made that task so difficult.

Serious intraparty challenges to incumbent presidents have typically required deep factional divisions. When Eugene McCarthy and then Bobby Kennedy ran against Lyndon Johnson in 1968, their candidacies were fueled by opposition to American involvement in Vietnam. When Ted Kennedy took on Jimmy Carter in 1980, he drew on a widespread sense that the president had mismanaged the economy and betrayed the legacy of the New Deal. The situation was far less defined this time around.

Certainly, Biden was unpopular among the electorate. The reasons are a bit mysterious: he presided over growth rates that are the envy of other rich democracies and passed big-ticket legislation, above all the mammoth Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). But inflation clearly took its toll. Peaking above 9 percent in 2022 before slowing to its current rate of 3 percent, it was the electorate’s top concern by some distance. To combat inflation the Federal Reserve kept interest rates high, making it harder to secure a home or business loan. Then there was the president’s age, which voters have been concerned about for years.

But electoral liabilities are one thing; party support is another. Biden long retained broad, if not ardent, backing across the Democratic big tent. He tended to his political constituencies, taking special care to reach out to Black and Hispanic elected officials and organized labor. His first White House chief of staff, Ron Klain, was a greater ally to progressives than his predecessors under Obama. For all the danger signs, moreover, Biden’s erosion in the polls was sharpest among those least likely to vote: the youngest survey respondents, those who stayed away in 2020 or 2022, and those who weren’t following the presidential race—hardly a potent basis for a challenge. Dean Phillips, a third-term House member from Minnesota, was the one “normie Democrat” who ran against Biden in the primary; he specifically cited the president’s age. For his troubles he earned widespread annoyance, five delegates, and a political future as a trivia answer.

The party was broadly united on matters of policy, too. Democrats agree on bolstering the safety net and protecting abortion rights, and the Biden administration also built consensus around engineering a carbon transition and forestalling the rise of China. Its agenda bore the hallmarks of the liberal nonprofits in which so many Biden staffers marinated, starting with National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan. Jennifer Harris, another National Security Council official, described the Biden administration’s industrial policy as “a vindication of the idea that democracy is as much about economic agency as political agency.” Whatever the merits of that assertion, they could point to real accomplishments. Bills like the CHIPS and Science Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law won a modicum of Republican support; others, like the IRA, passed with near-party-line votes.

There were disagreements, of course. Moderates grumbled that Biden’s appointees to agencies like the Federal Trade Commission too imperiously regulated Big Tech and other industries. Progressives like Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders pined after the ambitious welfare-state spending that was scrapped from the IRA as the price of obtaining assent from Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin.

The most wrenching divide was Gaza. When protesters called for an immediate cease-fire and withdrawal of US military support for Israel, they struck at a fault line running through the Democratic coalition. The stakes were made clear in June, when an AIPAC-backed primary challenger named George Latimer defeated Jamaal Bowman, a second-term House member who excoriated “the genocide that’s happening in Gaza.” Yet for all its intense salience—particularly among Muslim, Arab, and Jewish voters—polls suggest the war is not a major voter concern, even for young people. The “uncommitted” campaign run by antiwar activists to push Biden on the issue amassed barely one percent of delegates. This isn’t 1968.

So we arrive at the Democrats’ predicament. Biden was clearly not the best candidate to stand against Trump in 2024. Yet there was no incentive for anyone to mount an intraparty challenge against him. The real question, then, is not why the president took so long to bow out—that story will get told in time—but rather why the party could not produce a superior nominee in the first place. The crisis that engulfed the Democratic Party was about Biden, to be sure—but only proximately so.

The roots of that crisis can be found in two historical developments. One is the presidentialization of American politics, which gathered pace through the twentieth century. The other is the hollowing out of the Democratic Party’s organizing capacity, which began in the late 1960s. Each development reinforces the other: as the presidency grows more powerful and the party hollows out, presidents escape from its fetters.

Martin Van Buren, a lawyer turned US Senator, established the model for the world’s first mass political party in the 1820s in New York. The “little magician” and his allies formed an organization known as the Albany Regency, which dominated state politics, nominating party members to office, doling out government jobs and contracts, and publishing a network of newspapers. The Regency valued party loyalty above all else—unlike their opponent DeWitt Clinton, who made deals with Federalist opponents. When Andrew Jackson ran for president in 1828, Van Buren saw a chance to take the model national. He envisioned a Jacksonian Democratic Party that would unite “the planters of the South and the plain Republicans of the north” around Jeffersonian principles—and keep discussion of slavery off the federal agenda, thereby forestalling threats to the peculiar institution. True to its Empire State lineage, it would be locally rooted, highly participatory, and dedicated to the principle of the party over the man.

Starting in 1832, Democrats chose nominees at conventions, which state parties dominated for well over a century. As an 1884 newspaper account explained, “the National Convention has only a delegated authority and no power of coercion over the party in any State.” At first candidates rarely campaigned on their own behalf. Instead, local organizations ran the electoral machinery. They made up platforms, conducted campaigns with brass bands and torchlight parades, and, in the age before secret ballots, printed party tickets. In office, presidents had to placate rivals across the cabinet. As five incumbents across the nineteenth century discovered, renomination was not guaranteed.

That all changed with time. In the final decades of the century, national party committees came into their own as permanent rather than ad hoc organizations.1 Rather than serving at the mercy of state bosses, sitting presidents and even presidential nominees now had personnel and funding to run their own campaigns and make their own political weather. In 1955 Dwight Eisenhower set up a campaign school to teach all forty-eight GOP state chairmen such topics as the “fundamentals of campaign organization” and “effective utilization of advance men.” The chairmen in turn trained their own county chairs. Many presidents, especially Republicans, have engaged in this form of party-building.2

Meanwhile, the federal government expanded its reach. During the Progressive Era, the New Deal, and the early cold war, it inexorably encroached on traditional state and local prerogatives in tasks ranging from infrastructure development to labor law and poor relief. Presidents’ political standing rose in turn. Established in 1939, the Executive Office of the President became a nerve center for White House operations. And the emergence of the country’s modern security apparatus, particularly its nuclear arsenal, likewise broadened executive authority—a phenomenon that Garry Wills called “bomb power.”3

Yet the old bulwarks of party power hardly disappeared. Governors, senators, and big-city mayors still controlled state delegations to the national conventions. In the New Deal era, urban machines—most prominently in Chicago but also in cities like Pittsburgh and Albany—took popular liberal stances on national issues (what happened at home, where group conflict was more intense, was a different matter) and put to work the resources that federal programs channeled their way. These players all demanded favors from presidential contenders, whether in appointments or policy. More to the point, they nominated candidates whose political fortunes might raise their own.

State parties generally chose their national convention delegates through opaque processes with little public input. The first presidential primaries occurred in 1912. But most of them were nonbinding “beauty contests,” to use the nickname from the time: useful for assessing candidates’ strengths, but with no bearing on delegate selection. Only in the 1950s and early 1960s did the national party start issuing formal requirements for seating state delegations. As the civil rights movement grew in strength, northern Democrats, increasingly committed to stopping Jim Crow, targeted lily-white delegations from the South. And so the national party implemented minimal standards of loyalty, eventually ordering state parties to “assure that voters in the State, regardless of race, color, creed, or national origin, will have the opportunity to participate fully in Party affairs.” Even then, the processes for selecting delegates put insiders at an advantage, including in the north. The system was riddled with capricious and arbitrary practices: procedures hidden in inaccessible rulebooks, meeting times unpublished, quorum requirements selectively enforced, and rampant proxy voting.

Its intransigence was made clear in Chicago in 1968. Because Johnson withdrew months before the convention, most delegates supported his vice president, Hubert Humphrey, while a minority from the antiwar faction that had backed McCarthy and Kennedy (assassinated two months earlier) looked for an alternative candidate and pushed a more dovish stance on the Vietnam War. From the White House, Johnson worked his connections in the hall to prevent any compromise. Outside the International Amphitheatre, his ally, Mayor Richard J. Daley, set the police on demonstrators.

Searching for a way to break the majority arrayed against them, the antiwar forces launched a series of formal challenges to state delegations, questioning the procedures through which they’d been selected. They lost almost everywhere. Their efforts to amend the platform also ended in failure: the plank as adopted declared that unilaterally withdrawing from Vietnam would allow Communist “aggression and subversion to succeed.” Yet even as the party “regulars” prevailed in the hall, their violent implacability reflected a broader legitimacy crisis. As Elizabeth Hardwick wrote in these pages, “Few had realized until Chicago how great a ruin Johnson and his war in Vietnam had brought down upon our country.”

The insurgents secured one victory. In a chaotic late-night vote, delegates approved setting up a committee to reexamine the delegate selection process and promulgate reforms. The McGovern-Fraser Commission, as it came to be known, included no genuine representative of the New Left, but much of the body was shaped by the social movements of the period, and many had cut their teeth on McCarthy’s campaign. They championed what he described as “democracy in party procedure as well as in public policy.” Party regulars and the hawkish wing of the AFL-CIO ineffectually resisted.

In short order the commission proffered eighteen new standards for the selection of state-level delegates. State parties had to make their procedures transparent, timely, and accessible to all Democrats; automatic “ex-officio” delegates were banned; and aspiring delegates had to declare their presidential preference (or uncommitted status). Within a few years these new standards gave shape to our current nominating system: a gauntlet of state-level primary contests, with a few caucuses sprinkled in.

This outcome was largely unintended. Though their views were varied and frequently hazy, reformers generally wanted delegates to be chosen at state-level conventions where activists and social movements could participate effectually. The commission’s chair, Donald Fraser, had made his career in such a setting, Minnesota’s Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party; he later called primaries “awful things” for robbing parties of control over nominations.

The McGovern-Fraser ethos, in other words, was participatory but not antiparty. And yet its recommendations weakened party actors. The main reason was practical: direct primary elections offered the cheapest and least onerous means to meet the new participatory requirements. In the system that emerged by the mid-1970s and assumed something like its current form after the 1988 cycle, delegates were allocated to candidates in proportion to voters’ preferences in primaries, and pledged to support them in the first ballot of voting. Conventions were effectively rendered obsolete as deliberative bodies and turned into weeklong infomercials and networking events.

This marked a radical break in the history of the Democratic Party. Before reform, state and local organizations (and, in turn, their patrons) had largely called the shots.4 There was little pretense of internal party democracy, but the party apparatus played a central part, culminating in the presidential roll call at the convention. Once it became all about primaries and caucuses, a genie was let out of the bottle. Any argument that the convention should work its will, that delegates should debate the merits of each nominee, would henceforth be labeled undemocratic. Tellingly, as he struggled to save his candidacy, Biden wrote to congressional Democrats that “the voters—and the voters alone—decide the nominee.”

Disempowering delegates removed a bulwark that had kept presidents from dominating the party—especially incumbents seeking reelection. In the past, the most direct way for politicians to deny a renomination was through control over how delegates voted at the convention. Now that route was blocked.5 A time-traveler from the mid-twentieth century would be surprised that the crucial figures who pushed Biden to withdraw—above all, Pelosi and Barack Obama—owed their influence to personal stature, not their hold over state delegations.

Which brings us to a crucial irony. The antiwar reformers were spurred into action by their disgust at Johnson’s aggression in Vietnam, but they failed to build an effective counterweight to what Arthur Schlesinger would soon call “the imperial presidency.” If anything, they ended up further bolstering the president’s dominance over the party.

Nominations in the post-reform era have not entirely been candidate-driven free-for-alls. An expanded network of players in, and in many instances out, of the formal party—donors and “donor advisers,” interest groups and activists, pollsters and admakers—often coordinate to signal a favored candidate during the so-called “invisible primary” in the year prior to the Iowa caucus. Bill Clinton, for instance, allayed concerns about his Democratic bona fides at one such event in November 1991. Having salted the crowd with supporters, he evoked what The Washington Post called “his grandfather’s near-religious devotion to Franklin D. Roosevelt.” Money and endorsements soon followed.

But decision-making by party network has grown unwieldy, not least because that network has metastasized. Fulminations about Koch, Thiel, and Musk notwithstanding, the new superrich from tech and finance have donated handsomely to the Democrats and progressive organizations, motivated by social liberalism and, more recently, revulsion at Trump. Democrats have had the financial advantage since the first Obama campaign. The dollars have flowed ever more freely since the Citizens United decision in 2010. But they go more often not to formal parties but to “independent expenditures,” most importantly so-called Super PACs, which are forbidden from coordinating with candidates or parties.

Meanwhile, the traditional interest groups on the Democratic side, most importantly organized labor, have been displaced by a bevy of nonprofits, funded by the likes of the Ford and Open Society Foundations, a host of smaller family foundations, and middle-class activists. These entities seek to get “new paradigms” and calls to “think big” into the bloodstream. But given their tax status, they are typically barred from electoral politics—and unaccountable if things go sour. All the money and all the nebulous entities swirling around make it still harder for the party to carry out what Van Buren identified as its essential task: coordinating when the stakes are highest and aligning personal incentives with electoral victory.

As a precocious senator-elect from Delaware, Joe Biden entered national politics in 1972, at the dawn of the era of candidate-centered fragmentation. For all his rhetorical nods to the New Deal, he remains a figure of that individualistic era. His insular core team of advisers dates back deep into his senatorial days, including Ted Kaufman, Mike Donilon, and Klain. But he has nimbly shifted with the ideological winds. In 1988 and 2008, as the invisible primary worked its magic, he withdrew to keep his long-term prospects alive. When he finally did get the prize, it was through a primary contest that illustrates the modern party’s abject disorder.

In no effective or concerted sense did “the Democratic Party” decide its 2020 nominee. Elites in and around the formal apparatus—elected officials, poohbahs at interest groups and nonprofits, donors—were all deeply skeptical of Sanders. But rather than coalescing around someone else, they failed to winnow an overcrowded field. The nomination was hardly Biden’s to lose, not least after he placed fourth and fifth consecutively in Iowa and New Hampshire. Then, with the aid of Jim Clyburn, he overperformed in South Carolina, and in the three addled days that followed, moderates Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg dropped out almost simultaneously, giving Sanders-doubting voters a signal. Once Biden cleaned up on Super Tuesday, the race was effectively over. Disapproving Sanders supporters and approving political scientists alike saw the invisible hand of coordination.6 But the whole episode was marked by tardiness, contingency, and a seat-of-the-pants frenzy that belies any notion of strong party control.

Biden’s choice of running mate was likewise ad hoc. He picked Harris more because she was an African American woman and reformist prosecutor than for her Senate relationships. She struggled, especially in her first two years as vice president, with knotty portfolios, from voting rights to border management. Someone with deeper friendships across the party and surer judgments in the eyes of its leaders might have made succession less fraught. In the event, once Biden endorsed Harris, the Democrats rapidly buried their qualms (at least for now), posted coconut tree memes, and consolidated. It was the 2020 process played out far later and even faster.

The outer limits on presidential domination over the Democrats are clearer now than they were on June 27 (as is the contrast with the Trumpified GOP), and the case for the party’s vitality is stronger. In the nineteenth century, when the party printed tickets with the names of aspirants for office at every level, they all had reason to cooperate. This summer, when an enfeebled incumbent threatened to drag down everyone running under the party label, they briefly showed the capacity to do so again.

But the underlying dynamics that almost led to Biden’s nomination have yet to change. By elevating Harris to the top of the ticket based on her former boss’s endorsement, the Democrats merely accepted the logic of presidentialization. They seem delighted to have a candidate campaigning at full tilt. But that enthusiasm should not be read backward into the process of her selection.

The Democrats have new reasons to defend the venerable claim, recently restated by Jonathan Rauch in The Atlantic, that “nominations belong to parties, not to candidates.” Bolstering the role of parties in nominations will require building up capacity, at the DNC and in the state organizations. Democrats might even go further, fulfilling the unmet promise of the reform era to build a party that could restrain the presidency itself. In 1976 Leonard Woodcock, the head of the United Auto Workers, proposed that Democratic presidents “report annually, not only to the nation on the state of the union, but to the Democratic Party on the state of the party.” One might dare to imagine the scene: a year after securing the Democratic nomination as the byproduct of a crash-course collective effort, President Harris issues just such a report to the party that put her in power.